Customer Stories

Continuous Availability at IBM

What it means to run the cloud that supports very visible event sites.

Brian is a Senior Technical Staff Member and has been at IBM since 2001. His focus is on the development side. His counterpart, Rich, is a software engineer whose focus in on the infrastructure side. He’s been at IBM since 1989. Brian set the stage by describing the team’s two overriding concerns. “Our focus is on continuous availability. You should always be able to get to our web sites. Continuous availability is the lens by which we examine all our technical decisions. “Also, our business is different from most because we have hard deadlines. Things don’t slip for us. A lot of our priorities are driven by that fact. You can’t push back and say, ‘Sorry, you’ll have to move the US Open to a couple days later.’ That doesn’t work. I’ve tried.”

The IBM event cloud

The IBM cloud that the events team uses is, in fact, a hybrid cloud. Some of their workloads run in the public cloud, on SoftLayer, while others run in the private cloud, which is based on OpenStack. Currently, AIX makes up a large part of the infrastructure, along with SUSE Linux and Red Hat Linux. However, going forward, the team has decided to support a single platform, Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL). They are gradually moving their systems over, and bringing them under Chef management as they do so. Their development workstations are a mix of Red Hat Linux, Ubuntu and OSX.

The overall environment is complex. There is a test environment, a pre-production environment, which consists of two separate locations, and a production environment, which consists of seven locations. Each production location is treated separately. It’s not unusual to take a cloud location down for a week or even two weeks at a time, or to keep it at an older version, while the web site itself is always available.

About IBM

IBM sponsors many well-known sporting events, such as the US Open and the Wimbledon Championships. The IBM Continuous Availability Services – Events Infrastructure (CAS-EI) is the team that operates and manages the very popular web sites for these events. For example, during this year’s Wimbledon Championships, the team delivered half-a-billion page views during the two-week tournament. In this article, IBM CAS-EI members Brian O’Connell and Rich Bogdany talk about what it means to run the cloud that supports these very visible sites.

Part of our infrastructure hasn’t been ported to Linux and Chef, yet. I keep seeing people re-doing things because they’re doing it manually. I keep saying, I can’t wait until that’s on Chef so we’re not doing that.

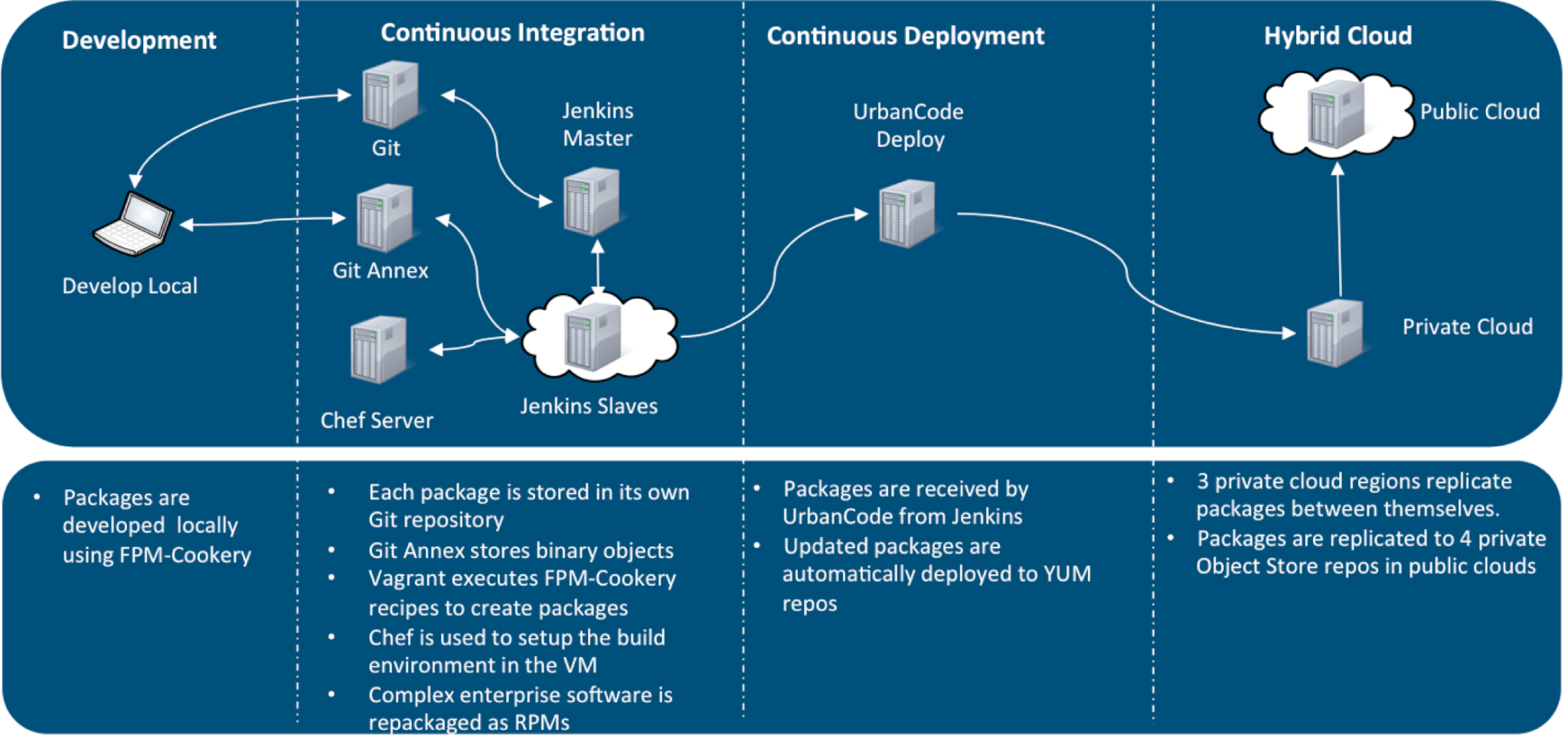

The event infrastructure automation stack

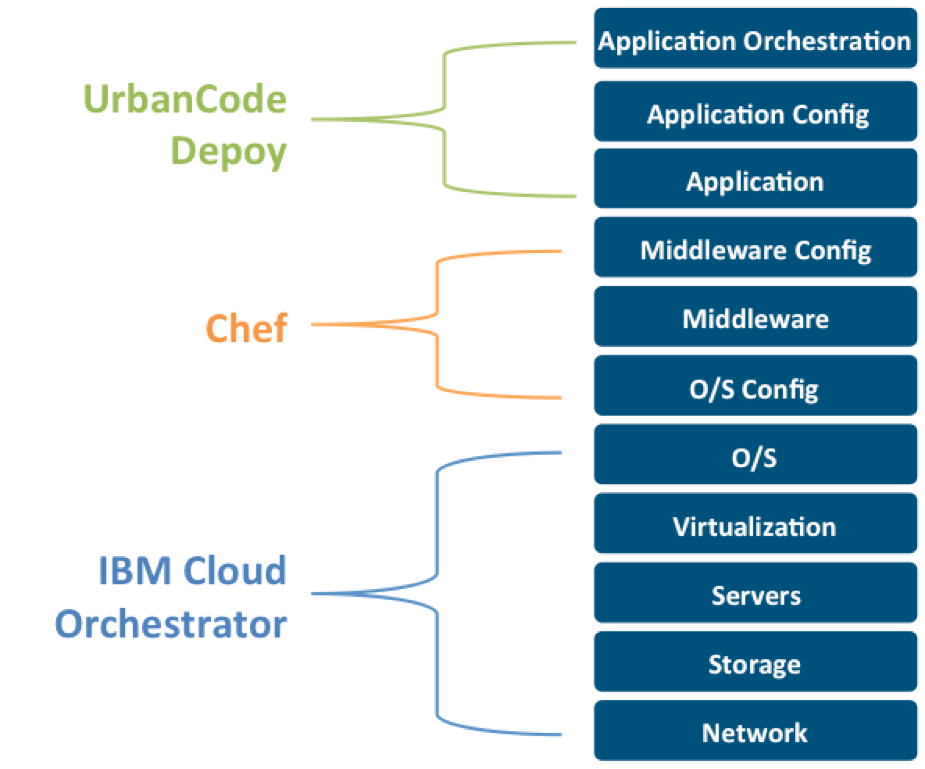

The automation stack is made up of three different products, each with its own area of responsibility. The following diagram shows the stack, and what each product does.

Rich described the role of IBM Cloud Orchestrator (ICO). “The main functionality that IBM Cloud Orchestrator provides is the operating system (OS) provisioning. We’re using KVM virtualization. ICO also controls the hardware. It lets us allocate disk and networks and the virtual servers. It’s the whole virtualization layer. It does a little bit of orchestration just to get the Chef process kicked off.”

Describing the rest of the automation stack, Brian continues, “ICO hands it off to Chef. Chef manages the OS configuration, installs the middleware and does any sort of middleware configuration that’s required. We use the same cookbooks for both our public and private cloud.

“After that, we hand it off to our top layer, which is UrbanCode Deploy (UCD). All our subject matter experts, including ourselves, have access to this tool, to either push out applications or application configuration updates or to do things like updating Chef roles. (We consider that a deployment). All of our deploys are the same, whether it’s an application or a Chef update.”

Treat everything as code

If automation is to be truly effective, everything must be treated as code. The IBM team keeps their assets in GitLab. They use Packer to generate images for their public cloud, their private cloud, VirtualBox, and VMware, all from a single source.

Anything installable that’s pushed through the pipeline, whether it’s SSL keys or binary files, is packaged as an RPM file. To create the packages the team uses FPM and fpm-cookery, which helps automate FPM. The RPM packages are deployed to an RPM repo, where they’re available to all the nodes. The relevant Chef cookbook is updated to point to the new RPM.

Team members do their development locally, then commit their work to source control. A commit triggers a Jenkins job, which uses Vagrant and Chef to spin up a build instance, execute fpm-cookery, and then build the RPM package. That package is then deployed by UCD.

Choosing Chef

The events team has used automation, in some form or another, since its inception. Brian says, “Our team was formed in preparation for the 1998 games in Nagano. We also delivered the 2000 games in Sydney. So, we’ve been around for a long time, delivering these sporting events.

“We have built, over time, a lot of automation, such as perl scripts, to do our jobs, but there were problems. Some scripts were run in one place, to bring up one piece of the infrastructure, and other scripts were run in another place to bring up a different part of the infrastructure.”

We need a fully automated build-and-converge system like Chef that can verify that everything is in place the way it should be…

Rich talked about his own experiences. “I automated a lot of our infrastructure in a home-grown, shell script framework over 10 years ago, using templates. I would try not to change nodes. I would try to change the code first. Obviously, the frameworks that are available now are much more sophisticated and it’s much easier to get other folks involved. That was lacking in what we were doing before. I’d have to maintain the scripts because it was hard to share them.

“Another significant feature that was lacking was testing. I couldn’t test anything we were changing beforehand other than to try it on a test node. This whole change to a formalized testing methodology is relatively new for me, but I definitely see the value.”

Brian was first introduced to Chef in 2013. “We got into configuration management, I don’t want to say accidently, but I was at an IBM conference, and there was an IBM product team talking about IBM Cloud Orchestrator and how they had added some Chef integration to it. They seemed really excited about it, so I thought I should figure out what Chef is. I started learning about Chef and we also had a Chef consultant work with us for a few days.

“For us, what we mean when we talk about DevOps is that we want our customers to be able to deploy things at their own pace, and we want to help them meet their business drivers. That’s our interpretation of it. It’s strongly on the deployment side. (Customers are internal IBM development teams.)

“My view is, to get us there, we need a very strong and stable infrastructure. To achieve that, we need a fully automated build-and-converge system like Chef that can verify that everything is in place the way it should be, so we don’t shift our time from doing deployments ourselves to chasing down why a customer deployment failed. That’s why we didn’t just take a deployment tool and put it in place. We brought everything under configuration management and made it convergent, so we have confidence that, yes, the customer deployment is going to work because everything is the way it should be. We don’t do changes manually. That can cause drift across our nodes.”

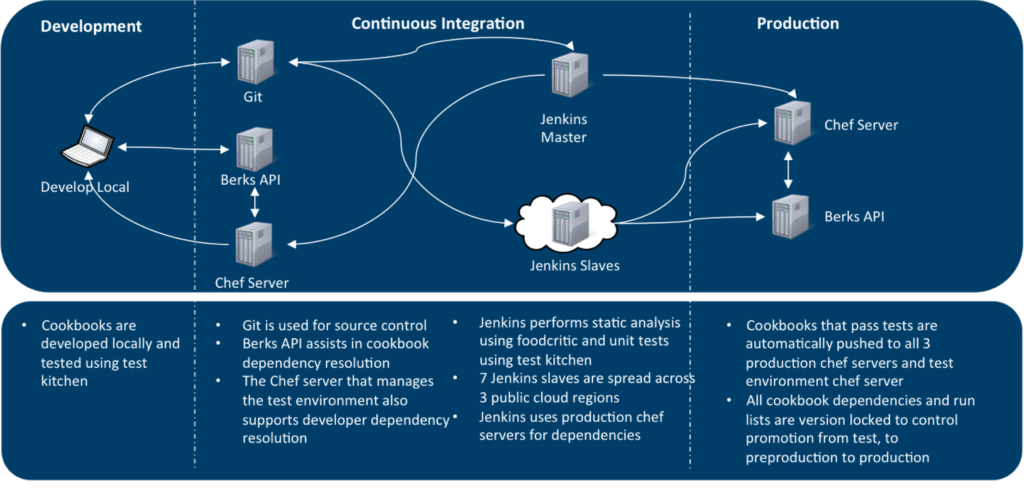

Deploying a cookbook

Chef cookbooks use the same deployment pipeline as applications. Here is the workflow for cookbooks.

The Jenkins slave agents run in SoftLayer, the public cloud, because SoftLayer can provide bare-metal nodes. This capability means there is no need for nested virtualization, which is not currently available in the private cloud.

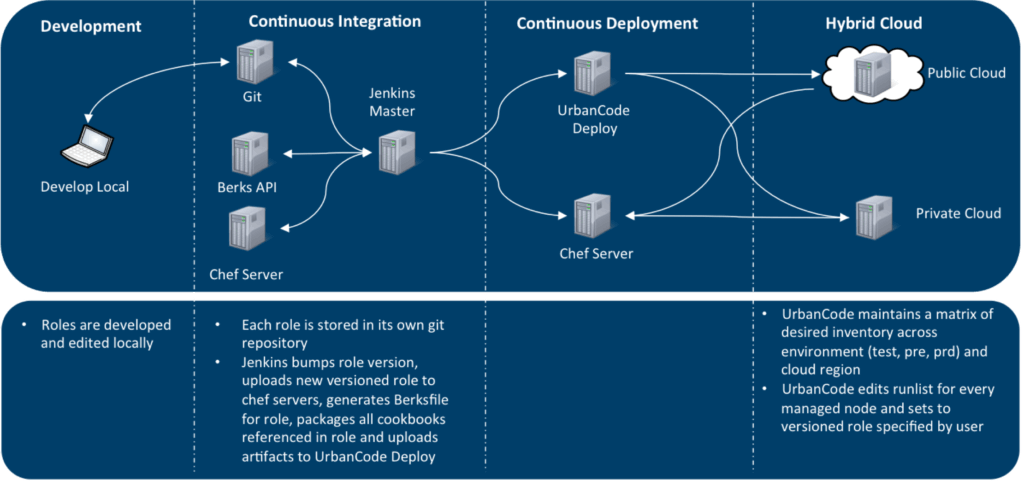

Versioned roles

The team began their work before Chef developed policy files, so they used a technique called versioned roles to pin particular cookbooks to particular environments. With versioned roles, you use role names that include a version number. This way the team can be selective about the changes each environment receives and, for the production environment, which is made up of seven cloud regions, they can keep different clouds at different versions. The UCD tool allows them to keep an inventory of which clouds are associated with which roles. Here is the workflow for roles.

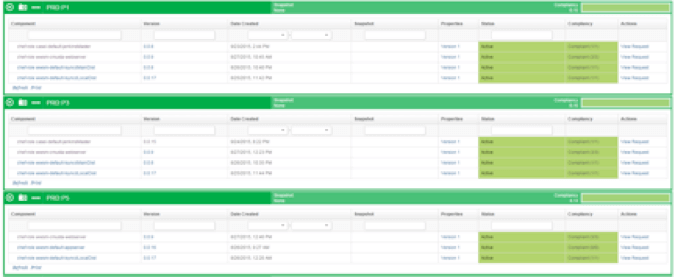

The following screenshot is an example of how the UCD inventory keeps track of a subset of the versioned roles across different private cloud regions.

Jenkins, in combination with scmversion, takes care of naming the roles and of incrementing the version number. UCD updates the run-list on the node to set it to that versioned role.

UCD deploys versioned roles to both the public and private cloud. It also modifies the node attributes on the Chef server. UCD does this by overriding the run list and converging the node.

Brian explains the approach. “Overriding the run list on the node is how UCD and Chef work together to set a node to a new desired state. This ensures that Chef and UCD are always on the same page about the desired state of a node.”

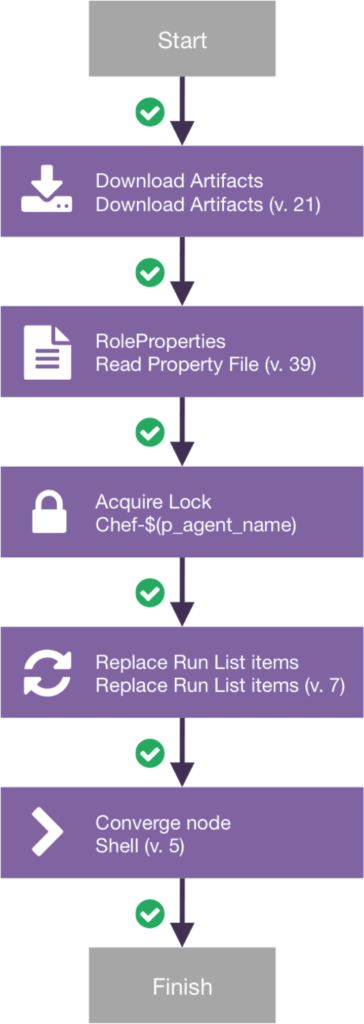

The process performs the following steps:

- A set of artifacts that is generated by Jenkins is downloaded. The artifacts describe the role and version to be updated as a properties file.

- The properties are read and made available to the subsequent steps.

- A global lock is acquired for the Chef client that runs on the target node. The lock prevents multiple updates from clashing with each other. (The lock is automatically released when the workflow finishes.)

- A regular expression and substitution is applied to replace run list items, which, in this case, are the role versions.

- The node is converged.

The following diagram shows the UCD process:

Packages

All binary files are treated as packages. Here is the package workflow.

Adopting Chef

As in most companies, the IBM event team includes people with a variety of backgrounds. Some people are new to source control or new to Git. Some have development backgrounds, while others have operations backgrounds. Rich remarked on how the first step is rethinking how you approach a problem. “You have to change your mindset. Historically, our team would fix problems manually on individual nodes. Okay, but the next time you rebuild that node it’s going to have the same problem if you don’t fix the source of it.

“Just this morning, with Jenkins, we did something manually weeks ago and now we can’t remember why we changed it or how we fixed it. You’ve got to get to that mindset where you have to change the code first. That’s definitely the first hurdle to get over.”

To bring everyone up to speed, the team uses Chef to bootstrap a workstation setup, some Chef training, whether in person or through Learn Chef, individual mentoring, and code reviews.

Setting up the workstation

To ensure that everyone’s workstation looks the same, the team has a standard way of setting up the Chef development environment. Team members go to a wiki page that gives them a single command to run. That command downloads Chef and then Chef itself sets up the workstation. Brian says, “There are also some links to the online Chef training, which we encourage people to go through. We also have some links to some Ruby primers. Because not everyone is familiar with Git, the team has its own helper gems. For example, team members can update all the cookbooks with a single command.”

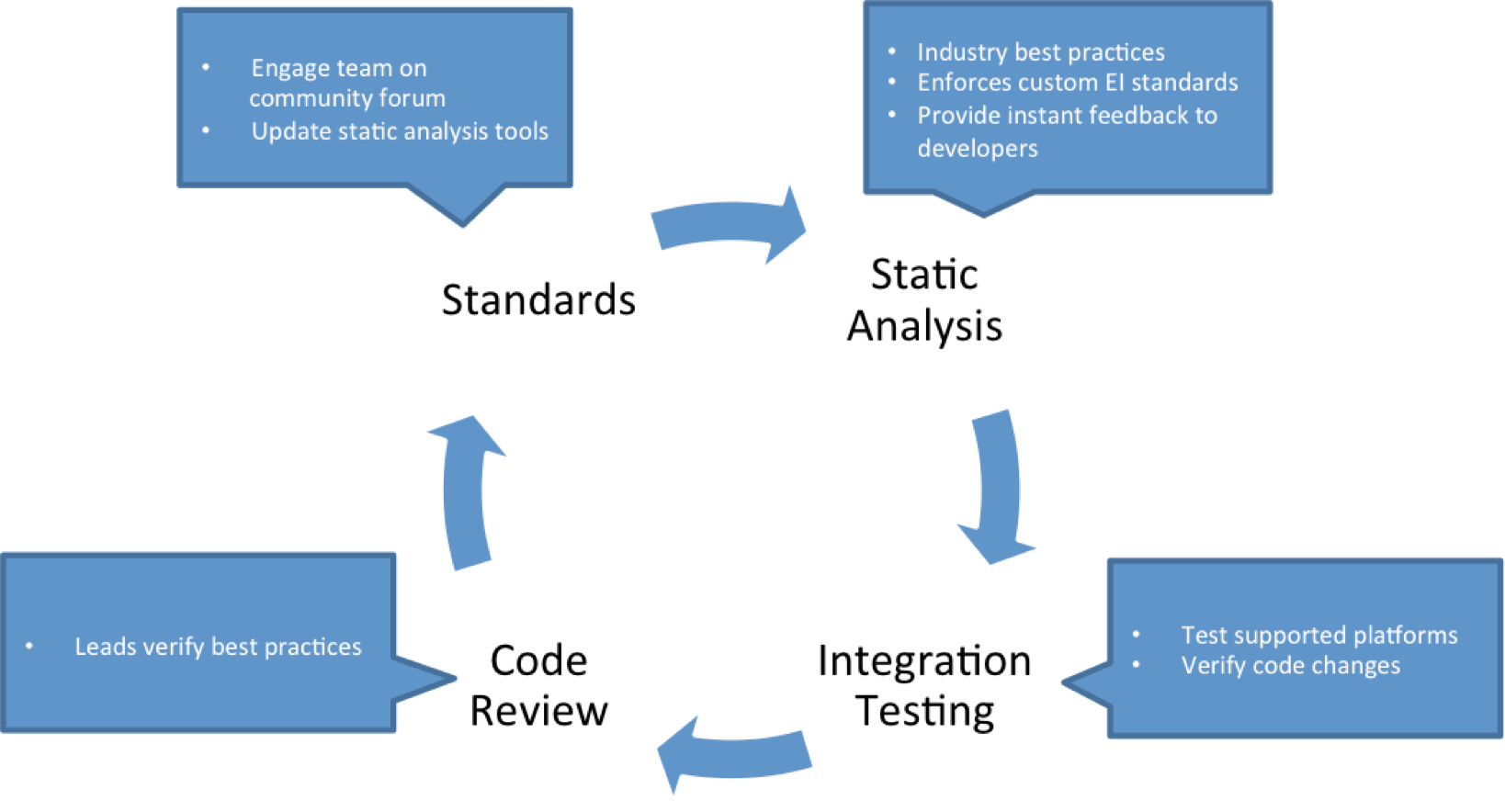

Achieving reliability

The event team uses a combination of testing, code reviews, and personal engagement to create reliable cookbooks that conform to a set of standards. Here is the process:

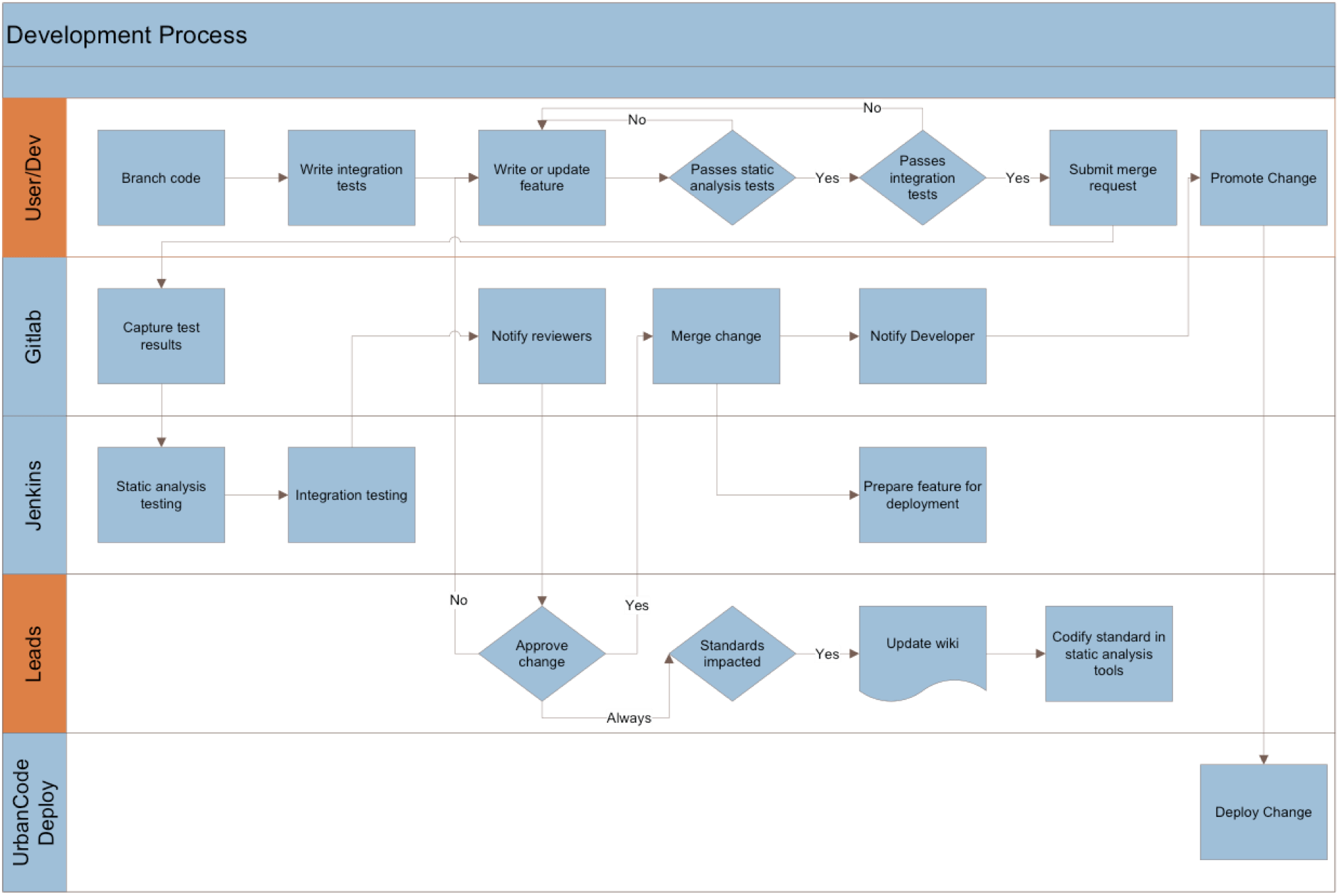

Brian explains, “We expect people to create feature branches. We expect them to write integration tests. We prefer that people write their tests first, although we can’t really enforce that. Do your red/green development. Write your ServerSpec test and then write your feature to make that test pass.

“Before you submit something, we provide tooling so that when you test a cookbook locally, it’s tested the same way as in the pipeline, so you’ll know ahead of time if the cookbook’s going to pass or not.

“Assuming that it passes, you submit your merge request, GitLab tells Jenkins to run static analysis tests and integration tests, and notifies people that there’s a merge request waiting. Either the merge is approved or it’s not. If it’s not, we ask ourselves if the issue impacts our standards. If it does, we create a story and add it to our static analysis. If it’s approved, the change can be merged and the person is notified. Jenkins will then send the updated cookbook to the Chef server. It’s up to the person to promote the change through UCD and push it out.”

Here is a more fine-grained view of the development process:

Rich commented on the time it takes to get used to the team’s approach to testing. “Testing, putting all that effort into writing all those test cases, can be hard. There’s a lot of test cases to write. Sometimes there’s more test code than the cookbook itself. That’s another one of the hurdles to get over.

“The testing is worth it. Part of our infrastructure hasn’t been ported to Linux and Chef, yet. I keep seeing people re-doing things because they’re doing it manually. I keep saying, I can’t wait until that’s on Chef so we’re not doing that.”

Code reviews

Code reviews are important to the team. They help people learn how to write cookbooks, and they provide a good forum for giving feedback. In fact, the team moved to GitLab because it makes the code review process easier.

Brian says, “We try to have a very tight loop in the code review process. If we see something, and we think it should be done in a certain way, we open a story to write a Foodcritic rule to get it in our development environment. We have, probably, 15 or 17 Foodcritic rules to enforce our various standards. For example, we need to examine the readme to make sure attributes are documented.

“We’re also in the process of adding RuboCop to our pipeline, as well. What’s nice about RuboCop is that, for standards that are debatable, it’s nice to have an authoritative source that isn’t someone on the team. When you’re saying, “No, it’s two spaces, not tabs” you can point to the rules in RuboCop and say, “We’re going to go with that.”

What’s Next

Along with migrating the rest of their infrastructure to Red Hat Linux and Chef, one of the team’s priorities is to increase the number of customers who are in charge of their own deployments. Brian says, “We already have customers who can push the deployment button but they’re so close to our team they understand how things work. Now we’re broadening out to the rest of our customer base.”

Of course, there’s no lack of things to do. Brian says, “We’re always going to be iterating and improving. We’re still trying to figure out how to get all our customers on board, and still build everything repeatedly and easily. Let me put it this way, our backlog is growing, not shrinking.”